Roundup! A book event, a cool podcast, gardening tips, TV and fiction recs and much more!

Hello! I hope you are doing OK and taking care of yourself. That’s a pretty tall order at the moment and if you are taking on even more — i.e., trying to help others and your communities — I’m grateful to you.

I’ve got a roster of good or potentially interesting things I want to mention, but before I get to that, I want to say this: If you are going to be protesting this weekend or at any other time, I’d strongly urge you to turn off biometric access to your phone (if you bring a smartphone at all, that is), and also check out this list of other tips from EFF and from veteran organizers.

So, here are 10 good or potentially interesting things:

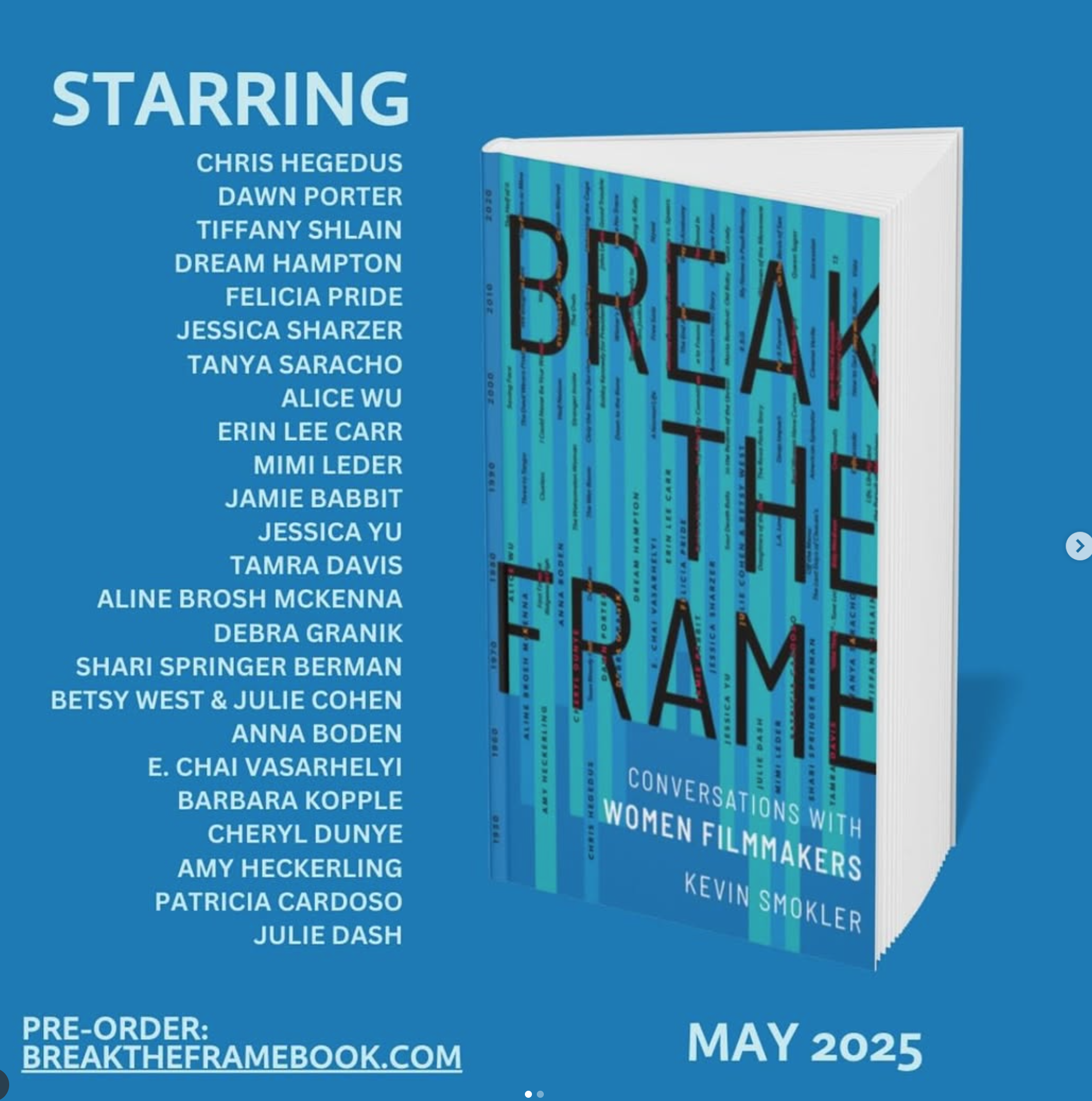

1. On Saturday, June 14 at 3 p.m. in Chicago, I’ll talk with Kevin Smokler, author of the excellent new book Break the Frame, an array of conversations with female directors. I can’t wait to talk to Kevin about his book, about the entertainment industry in general, and about my book Burn It Down (which this month celebrates its two-year book birthday, and I must once again thank everyone who supported my book in any way). Huge thanks to Jarvis Square Books, which will be hosting the event in an outdoor spot near the store in Rogers Park. If you want to register in advance, that’ll help the organizers get an idea of the head count.

2. I went on the Tilly’s Trans Tuesdays podcast to talk about the excellent Star Trek: Strange New Worlds episode Ad Astra Per Aspera. I love chatting with Tilly and Susan Bridges, and the conversation about this episode in particular was meaningful on so many fronts. It’s a three-part podcast, and the final installment comes out next week. Thanks for having me on, Tilly and Susan! You continue to be the best, and our chats are always a wonderful experience. (Side note: ST: SNW, which I enjoy a lot, returns on Paramount+ July 17, and I highly recommend watching the Season 2 finale before diving into the new season.)

3. There aren't a ton of new scripted shows this month, aside from the BritBox offering Outrageous, a six-episode saga of the Mitford family in the 1930s. Six episodes, of course, isn’t nearly enough to convey everything there is to know about the infamous Mitfords, but it’s a start! And I’ve now seen the first two episodes of Outrageous, a smartly paced, intriguing drama that definitely has an outrageously good cast. I dug into Mitford lore and interviewed the star and writer of Outrageous for Vanity Fair last fall, and a lot of the ideas in the show — and in those conversations — are still very relevant. Side notes: BritBox TV has a lot of very good films and TV programs (including my beloved Line of Duty and the Agatha Christie adaptation Towards Zero). Other TV I’ve enjoyed lately: Lots of shows on this list, plus Dept. Q, Andor and my first watch of OG Roswell, which is bringing me face to face with a lot of semi-traumatizing late ‘90s/early aughts fashion trends.

4. Would you like soothing fare that celebrates kindness and creativity in front of your eyeballs? Probably yes?? Great news, then: The Great Canadian Baking Show — which is so, so good — and a couple of later seasons of the Great Pottery Throw Down are coming to the Roku Channel. Hooray! Longtime readers will know of my deep love for GCBS and will be familiar with my assertion that the Great Pottery Throw Down is even better than its pastry-driven peers (and the first couple seasons of GPTD should still be on HBO Max, or whatever they decide to call it next month).

5. A couple of notable new books I want to mention: Megan Greenwell’s Bad Company, a chronicle of the destruction wreaked by private equity, which is evil. I’m so glad the super-smart Greenwell took on this important topic. And Maris Kreizman’s essay collection I Want to Burn This Place Down (great book title for this tome, which is out July 1). Both of these excellent authors are doing tours, and Maris’ newsletter The Maris Review is gold if you want to keep up with things worth reading. (Speaking of this topic, Bookshop now has a way to buy ebooks! An excellent development.)

6. I read a LOT and I always get stuck trying to make lists of recommendations, because it’s easy for them to end up way too long! But I will mention a few books that I really loved lately: Prom Mom by Laura Lippman (I simply think you cannot go wrong with anything by Lippman, Denise Mina or Tana French in this particular realm of fiction); Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum; Ocean’s Echo by Everina Maxwell (she’s got two books set in the same universe, but they’re not sequential and I’d read this one first); Alien Clay by Adrian Tchaikovsky was typically fascinating (though my faves by him are the Final Architecture and Children of Time series); Murder by Memory by Olivia Waite; the Mossa and Pleiti mysteries by Malka Older; The Martian Contingency by Mary Robinette Kowal, the latest in her Lady Astronaut series (which is super great); and I’m a bit late to this, but I positively devoured The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley. History buff? For the moment we’re living through, I highly recommend every book by Adam Hochschild, and also the one-volume version of Emma Goldman’s autobiography, Living My Life.

7. Just a reminder that there’s going to be another Battlestar Galactica convention in September, most of the cast and creative team is going to be there again, and I personally can’t wait for this Creation event. I’ll be hosting and moderating again, and last year’s con was truly life affirming in the best possible ways.

8. I came across this Star Wars intro/crawl generator and this was a very, very fun way to waste some time.

9. I’m on the board of the survivor advocacy organization Callisto, which I wrote about here. Things are more stable financially than they were last fall, which is great (but nonprofits like Callisto can always use money, of course, if you know of anyone with some spare cash. Side note: Thanks to everyone who participated in my eBay charity auction this spring, which partly benefited Callisto — I’m so grateful!). The organization is looking for board members, and if that sounds like something you’d be interested in, there’s more information here.

10. Earlier this year, I had the good fortune to go on the JoCo Cruise and meet a bunch of great people and participate in some talks and generally engage in delightful activities. They asked me if I wanted to talk about something other than books or journalism or the entertainment industry as we JoCo-ed, and I said heck yeah! I love, love, love gardening, and I wrote this Google doc with a few tips and ideas (I post pics of my garden on Instagram main and stories, if that’s of any interest). What I had to say really involves — I hope — demystifying gardening for newbies, but the document also might be of use to folks who already garden. It’s not a comprehensive array of advice, of course; it’s just meant as some ideas or questions to think about, with a few bits of well-intentioned input from yours truly. Hope you dig it!

And finally: Fuck ICE. Abolish it.